For many of us who engage seriously with photography, we are unavoidably amateurs. We practice photography in our spare time and fund it through our main mode of employment. Without earning a living from photography, we lay no claim to professional status, although we may have ‘professional’ aspirations, and may even make a modest dividend from selling prints or similar.

For some, the term ‘amateur’ will have negative connotations. In this little post I want to argue that it is something we should embrace, a title that conveys significant dignity and, in some senses, status.

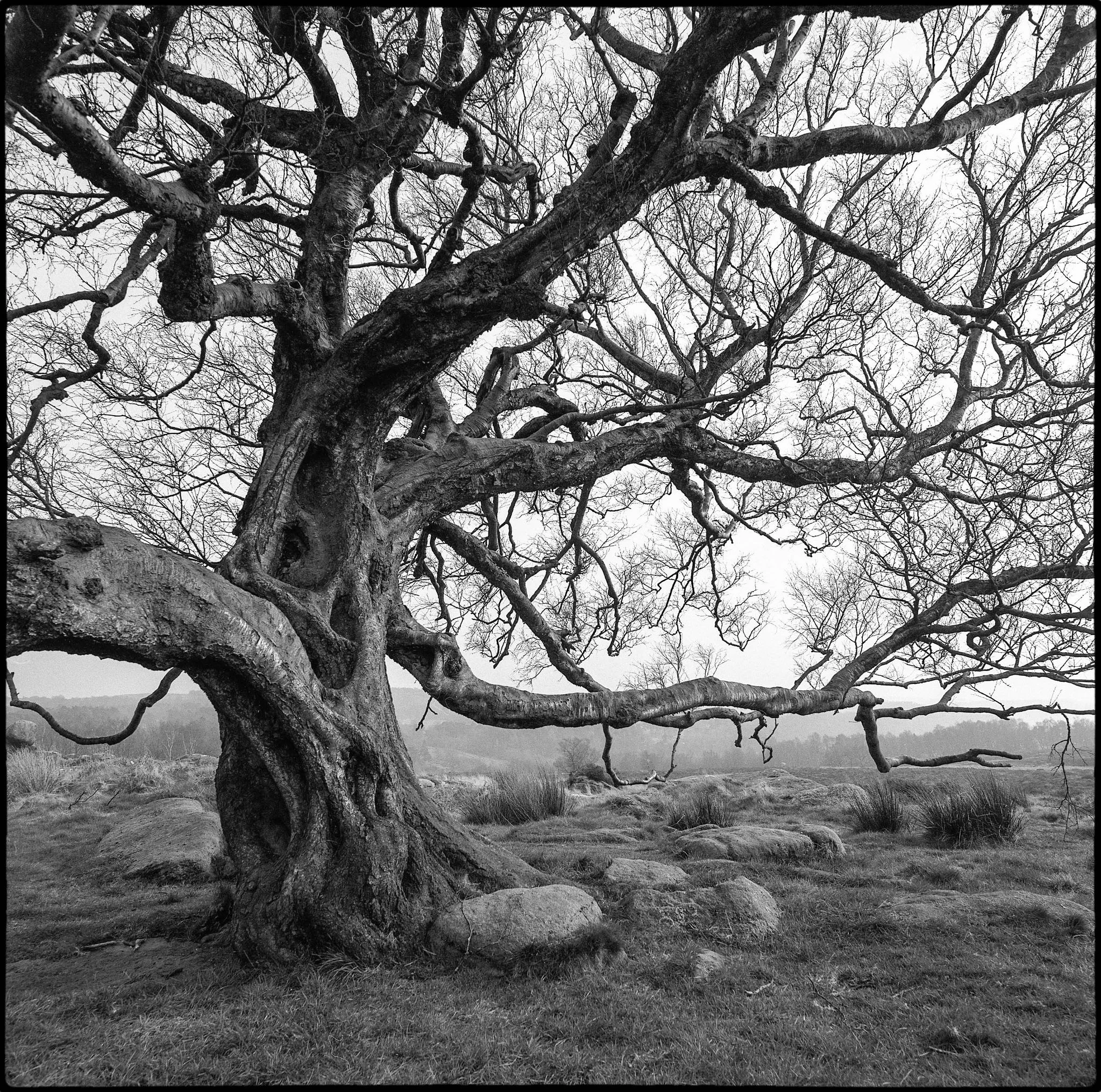

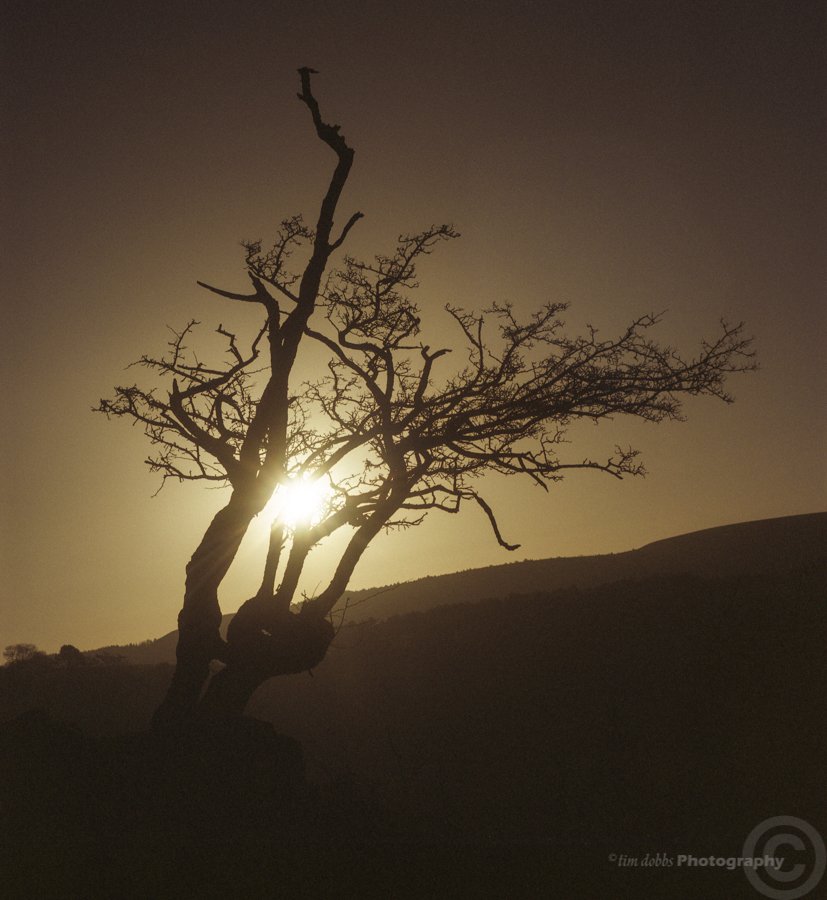

The latin root of the word points towards ‘lover’, and so we may think of an amateur as a lover of the medium. An amateur is someone who is able to pursue his or her interests unfettered by the needs of a client, or the conventions of an organised group. Indeed, many amateurs gain considerable expertise in niche areas of photography, simply because of the freedom to pursue exactly what they desire, and to direct their resources to such an end.

There is a tendency for a great many amateurs to look longingly towards professional status. Quality photographic equipment is marketed on the back of these desires. Ironically, much gear that bears the ‘pro’ label is in fact sold to an advanced amateur market. Professionals don’t have it easy. They are shackled by the demands of work and the necessity to marshal resources to make the bottom line pay. They cannot indulge in frivolous purchases, nor can they alter a work schedule to follow an experimental whim. In many ways, they are a lot worse off than those who would aspire to be them.

There is another, more subtle, reason why one might not actually want to aspire to professional status. To be a professional means to speak a very particular aesthetic language. We teach ‘professional’ methods and outcomes to our photography students, but what this really means is ‘make images like this’. Professional images look like, well, other professional images. This is a problem that is well recognised in the visual arts, a problem for which the term ‘academicism’ was coined. We can trace very precisely how the language of fine art developed from the French 18th century academies through to contemporary art today. For the painter in the first academies, to be an academician meant precisely to follow a set pattern of working that very much determined how the painting would turn out. This isn’t to say that there wasn’t any innovation, but the parameters in which you could work were highly codified.

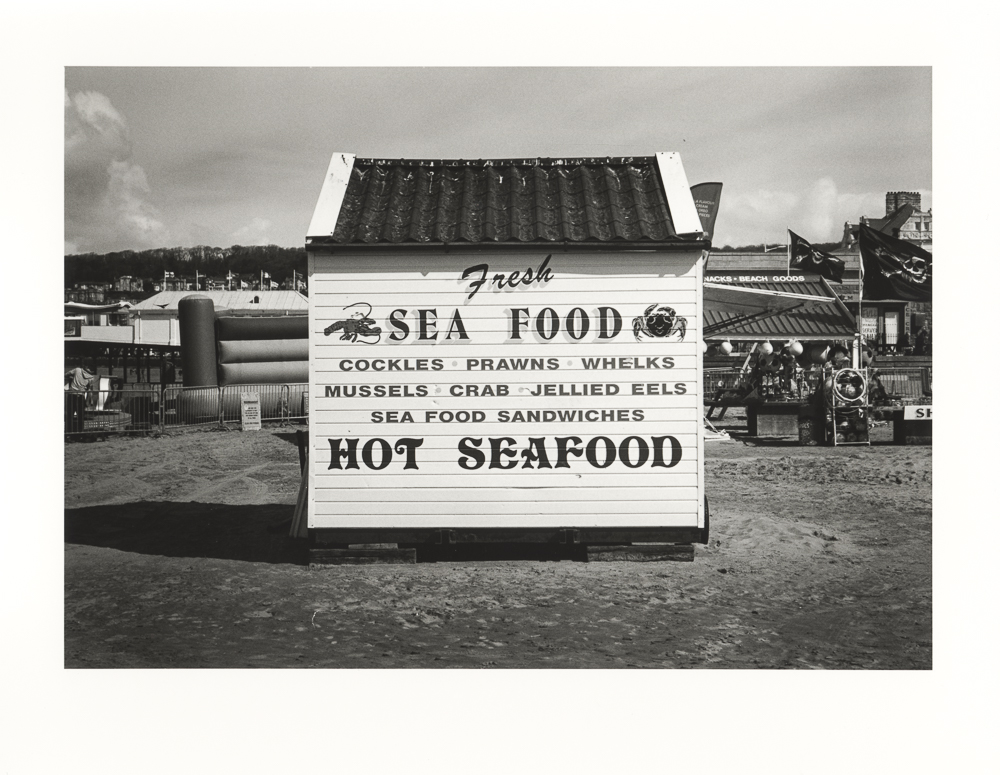

So, for me as a practitioner, the label amateur has a number of attractions. It reminds me of the considerable freedoms I enjoy, both in what I do with photography and how I do it. The medium itself has a special place in my philosophy of photography, and so I find the idea of a lover of the medium to be a description of great dignity. As an amateur, I am free to be as idiosyncratic as I like, an idiosyncrasy that has the potential to lead to aesthetic innovation.

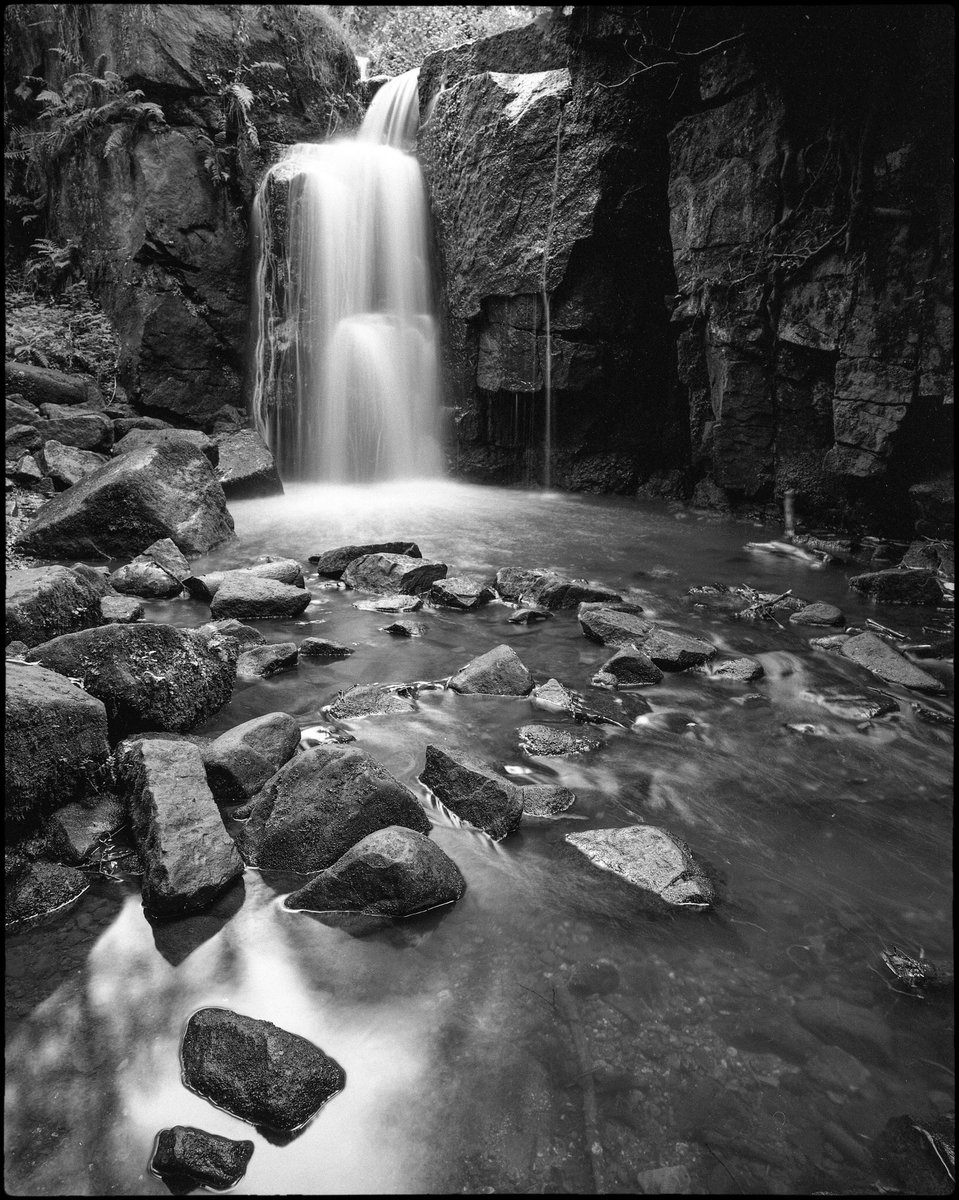

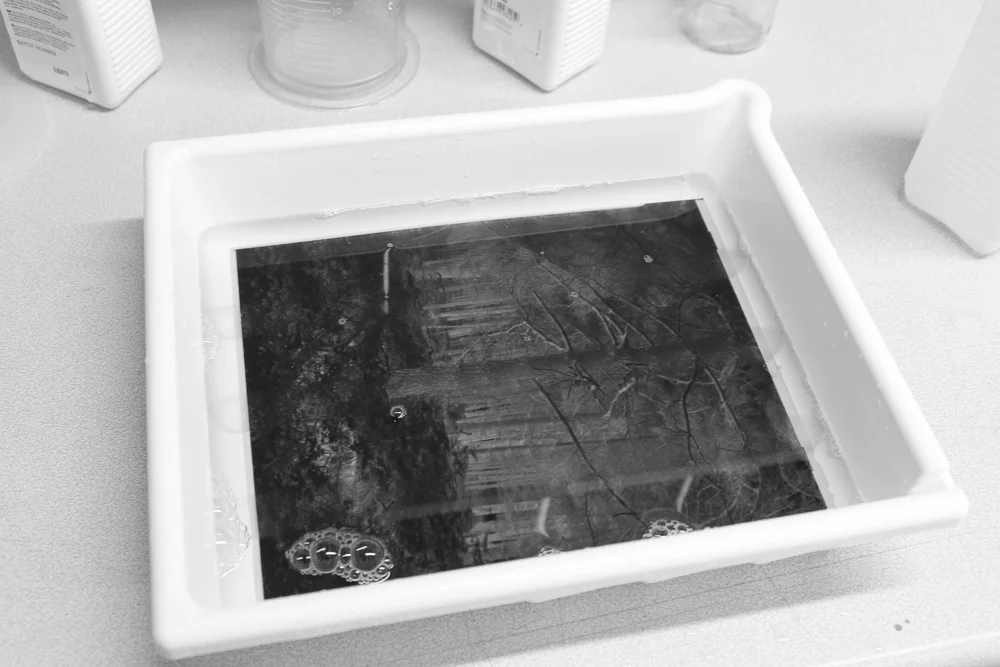

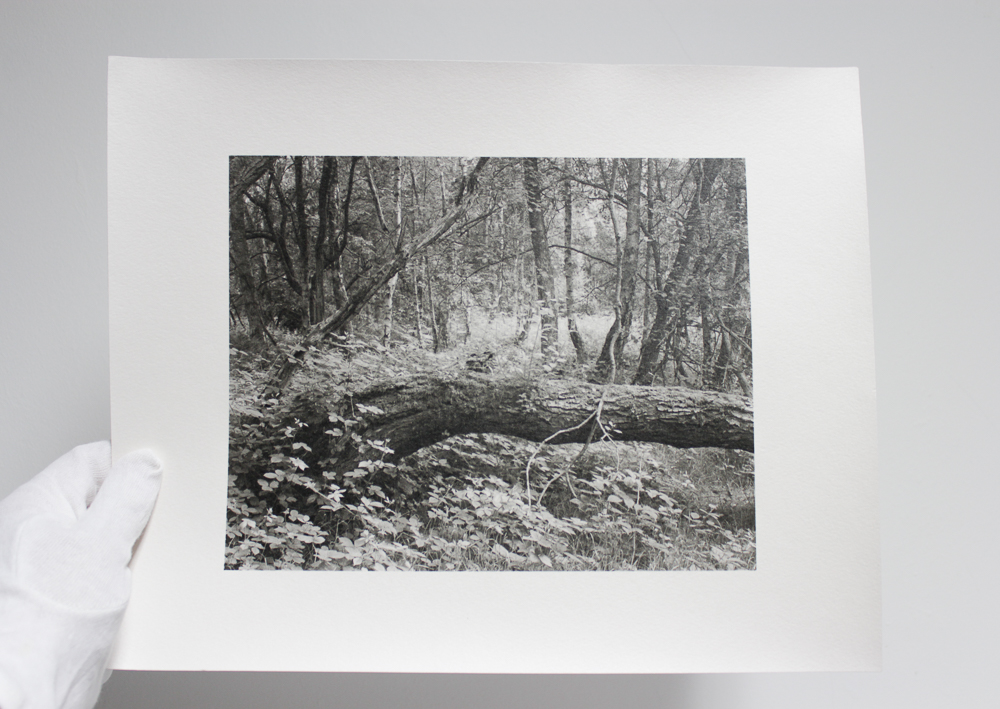

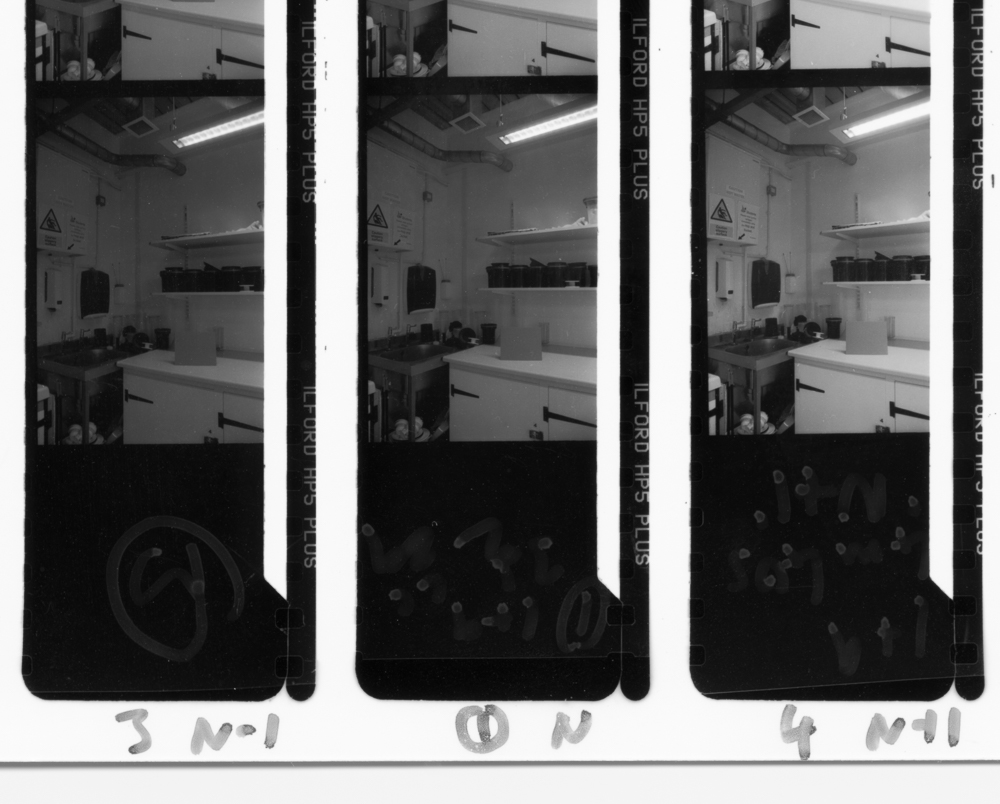

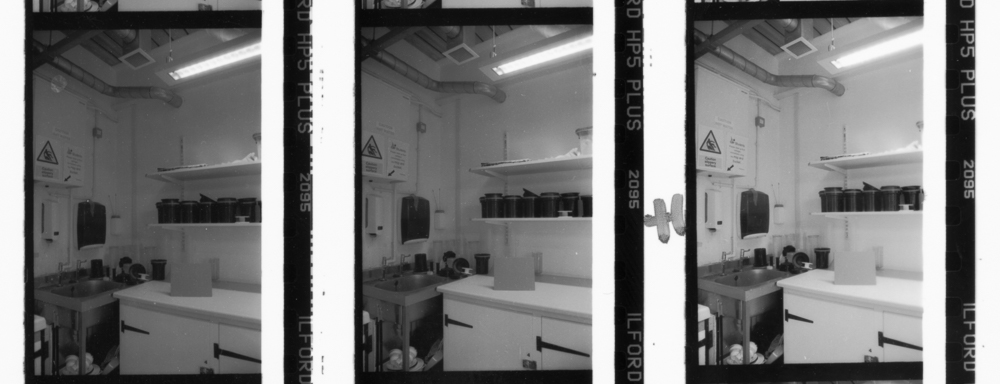

The recent rise in the popularity of analogue photographic media may well be a case in point. I can’t help but wonder whether a key attraction of film is precisely that it frees the photographer from so many of today’s picture making strictures and technical processes. This isn’t to say that film is somehow ‘not technical’ (it is, of course), but there is a directness and rawness that comes from an engagement with film that gives the user a sense of oneness with the medium. Additionally, film demands a commitment in time and inconvenience that a large majority of photography professionals have long turned their backs on in the name of working expedient. I don’t think it’s far fetched to say there is a relationship between the analogue resurgence and amateurism in my qualified sense.

Today, I am indeed happy to be an amateur.